When Good People Cross the Line: How a Correction in Canada's Real Estate Market Is Warping Industry Ethics

The once-thriving real estate industry in Canada is currently experiencing its worst slowdown in years. This financial strain is causing some professionals to bend the rules, raid trust accounts, and, in the most serious cases, engage in outright Ponzi schemes. Unfortunately, this crisis comes at a time when reputational damage to the industry is discouraging potential buyers. If clients can't trust their professional advisers, how can they feel secure that their purchase is a sound long-term investment? On the other hand, as a seller, can I trust that my agent is genuinely seeking the best offer for my property, or might they be steering my sale towards a friend who will then quickly resell it for a profit?

They don’t set out to become villains. They set out to pay the bills.

From the outside, the latest round of real estate scandals in Canada looks like a simple morality play: greedy brokers, shady mortgage “innovators,” and broker‑owners who treated client trust accounts like personal overdraft protection. But if you trace the arc back to 2020, a more uncomfortable picture emerges. A market that once rewarded hustle with six‑figure commissions has slowed to a crawl, leaving thousands of agents and brokers staring at the same balance‑sheet math as their most overstretched clients. They are spending too much on marketing to fight over a dwindling number of buyers; the commissions no longer cover their costs; they’re taking on too much debt, not enough cash, and there's no obvious way out.

A long boom meets a hard stop in Canadian real estate

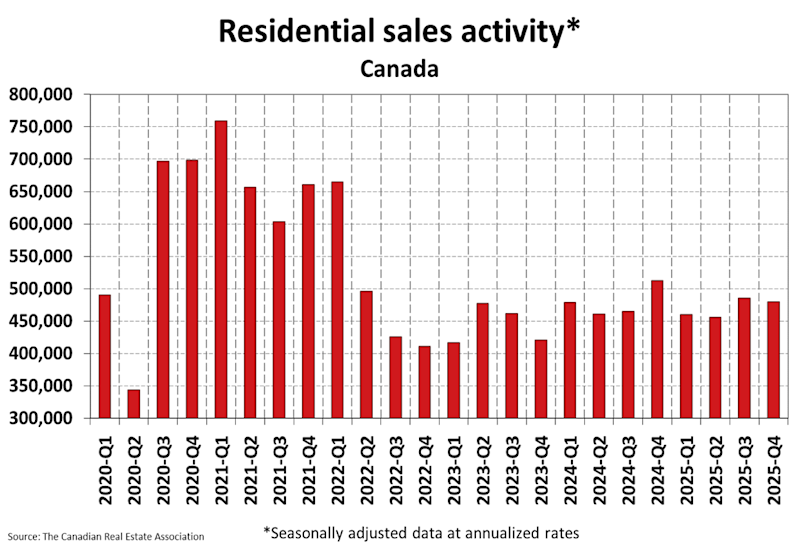

For most of the past decade, real estate in Canada didn’t just rise; it sprinted. Cheap money, pandemic‑era demand, and a culture that treated housing as both nest egg and national sport pushed sales and prices to dizzying levels. Then, in 2022, the Bank of Canada slammed on the brakes. A rapid series of rate hikes turned what had been the safest trade in town into a test for everyone tied to real estate in Canada.

By early 2023, premium property segments that had been the darlings of the pandemic were logging barely a third of their peak sales volumes. Transaction counts fell, financing costs jumped, and the pipeline of deals that paid the commissions, desk fees and lease obligations of the real estate Canada industry simply dried up.

In the hardest‑hit markets: Toronto, Vancouver, and high‑price pockets across Ontario and B.C., the pattern was the same: sales froze, inventory piled up, and once‑bulletproof business models began to look disturbingly fragile.

The pressure cooker for real estate intermediaries in Canada

A slowdown in real estate Canada is an abstraction on a chart; for people who live on commission, it is a line item called “pressure.” Real estate intermediaries share a particular vulnerability: they are both entrepreneurs and employees, carrying the fixed costs of the former and the income volatility of the latter.

For example, according to the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board (TRREB), 36,974 agents (53%) had no transactions in 2025, and that’s following the exit of 5,500 agents from the industry between 2023 and 2025.

Fraud analysts have long described the "fraud triangle," which consists of three components: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. In the context of the Canadian real estate market, pressure is the most evident aspect. Fewer property closings result in smaller and less frequent commission checks for real estate agents and mortgage brokers. Despite this, agents still have to cover ongoing expenses such as desk fees, CRM subscriptions, car payments, and marketing costs that they incurred when the real estate market seemed like a guaranteed success.

Broker-owners face even greater challenges, as they have to manage high-profile office leases, staff salaries, and marketing investments. Many of these costs are financed through variable-rate debt, which has become significantly more expensive to service.

Many agents face significant financial strain, especially those who invested their life savings in property. For example, rental condos may no longer cover their monthly expenses due to high mortgage rates. Additionally, home equity lines might be depleted to fund renovations or investment properties. The distinction between “just hang on a little longer” and “I can’t see how this adds up” becomes increasingly blurred. This troubling trend is evident across Canada’s real estate sector and is closely linked to commission-based real estate and mortgage work.

When opportunity meets empty accounts

Pressure alone does not lead to misconduct; however, it does create a strong motive for it. The opportunity for misconduct often exists within the inner workings of the real estate business in Canada, such as trust accounts, internal controls, and the less visible aspects of back-office operations that clients are unaware of.

iPro Realty Scandal (Ontario)

In Ontario, the iPro Realty scandal revealed how tempting it can be to misuse funds when financial situations become dire. Regulators allege that millions of dollars in deposits and commissions, which were meant to remain untouched in trust, were instead diverted to cover operational shortfalls and to pay investors. This diversion was concealed through the use of multiple accounting systems and falsified records. As the financial deficit grew, it became increasingly difficult to recover without admitting to the misconduct. It also became easier to label the situation as "temporary," while hoping for an improvement in the Canadian real estate market that never materialized.

The fallout from iPro Realty led to the province taking control of the Real Estate Council of Ontario (RECO) and dismissing its entire executive team. This action was taken to bolster consumer confidence in the industry's ethical practices, regulatory controls, and compliance oversight.

Save Max Brokerages (Ontario)

A similar story appears to have unfolded at several Save Max brokerages, where regulators say client trust funds were moved out to cover loan payments, taxes, and other expenses, with money swept back in before month‑end reconciliations. On paper, the accounts may have looked fine. Day‑to‑day, they were being used as a revolving line of credit that belonged not to the brokerage, but to buyers and sellers who trusted the real estate Canada system to protect their deposits.

These are not victimless “timing differences.” They are the point where financial pressure crosses the bright line of fiduciary duty. Yet it is striking how many of the people involved seem to have started with the same script: it’s just for cash flow, it’s just this month, clients won’t be hurt. In other words, rationalization, the third corner of the triangle, arrives not with a cackle, but with a shrug.

The exception: when fraud is the business model

There is an important distinction to make regarding recent issues in the Canadian real estate market. In some of the most egregious cases, particularly involving large-scale Ponzi schemes in the mortgage sector, the individuals at the center of these schemes did not simply succumb to wrongdoing due to pressure, they intentionally set out to deceive from the very beginning.

Promises of high, “guaranteed” returns, fictional bridge loans, and falsified statements were not just desperate attempts to improvise; they were integral to the business model. The aim was never to protect investors; instead, they were merely exploited as fuel for an enterprise built on lies.

Greg Martel / My Mortgage Auction Corp (B.C.)

Operating through his Victoria-based company My Mortgage Auction Corp. (MMAC), Greg Martel orchestrated what has been described as the largest Ponzi scheme in British Columbia's history. Between 2018 and 2023, Martel solicited approximately $301 million from over 1,700 investors, promising high-interest returns, sometimes as high as 100% annualized, on purported short-term bridge loans for real estate developers. However, an investigation by the court-appointed trustee, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), revealed that no such bridge loans ever existed. Instead, Martel used funds from new investors to pay back earlier ones while siphoning off millions to fund a lavish lifestyle, including luxury vehicles, private jets, and high-stakes stock options trading.

The scheme collapsed in early 2023 when the company stopped making payouts, leading to a bankruptcy that left "net losers" with roughly $149 million in losses. In 2025, the B.C. Supreme Court approved a landmark "clawback" process, allowing the trustee to recover roughly $71 million in "false profits" from "net winners", investors who unknowingly received more money back than they originally invested, to more equitably distribute the remaining assets. As of 2026, Greg Martel remains a fugitive with active warrants for his arrest in both Canada and the United States, his whereabouts unknown since he fled to Thailand and later Dubai shortly after the company’s collapse.

Stories like this are important not to excuse minor misconduct, but to illustrate the range of issues we face in the Canadian real estate industry. On one end of the spectrum, there are outright con artists who use real estate terminology to commit traditional fraud. On the other end are once-respected professionals who convince themselves that temporarily dipping into trust funds is a victimless way to navigate difficult times. Both types of behavior cause harm, but only one can reasonably argue that they began as "good people" before crossing the line.

A Tougher Market and a Tougher Reflection on Real Estate in Canada

None of this excuses misconduct. Clients’ deposits should not be treated as shock absorbers for brokerage profits and losses, and mortgage investors should not be used to cover the personal expenses of those in the industry. If we want to see fewer scandals making headlines in Canadian real estate, we need to do more than just name and shame the latest offender. We must confront the incentives that have turned certain individuals from "respected producers" into "regulatory cautionary tales."

This involves taking the connection between macroeconomic conditions and the risk of misconduct in real estate seriously. When home sales in key markets are at multi-year lows, yet the number of licensed agents and brokers remains at pandemic-era highs, the situation becomes unsustainable. With too many agents competing for the same business, the temptation to cut corners increases significantly.

There is a more constructive path forward for Canadian real estate. Implementing a clearer separation of client funds and operating cash, enhancing real-time oversight of trust accounts, and establishing capital requirements that reflect the industry's true cyclicality would all help reduce opportunities for misconduct. Additionally, fostering an industry culture that views the ability to decline a bad deal—or to avoid overextending—as a sign of professionalism, rather than weakness, is essential.

The Canadian real estate market will eventually recover; it always does. The real question is: what kind of industry will remain when it does? Will it be one that has confronted its own problematic incentives, or one that has merely become better at concealing them until the next downturn exposes them once again?